Hudson Hub Times

Bev Ocasek, June 7, 1989

“We pay real close attention to our dreams,” says artist Bernice Davidson Massey, explaining why she and her husband sold their car to buy an Amish buggy camper.

Four or five years ago Massey and her husband, James, had the same dream the same night. They dreams they were traveling around the country by horse and buggy. They drew up some plans and commissioned the Yoder family of Ohio to build a one-of-a-kind buggy camper.

Following their dream, the couple “study the maps and traveled on all the blue highways” from Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia to Mississippi, where they visited James’ 96-year-old grandmother. Massey remembers the best part of the year-long journey was meeting people along the way and collecting the aural history of the people they met.

The trip proved quite an adventure.

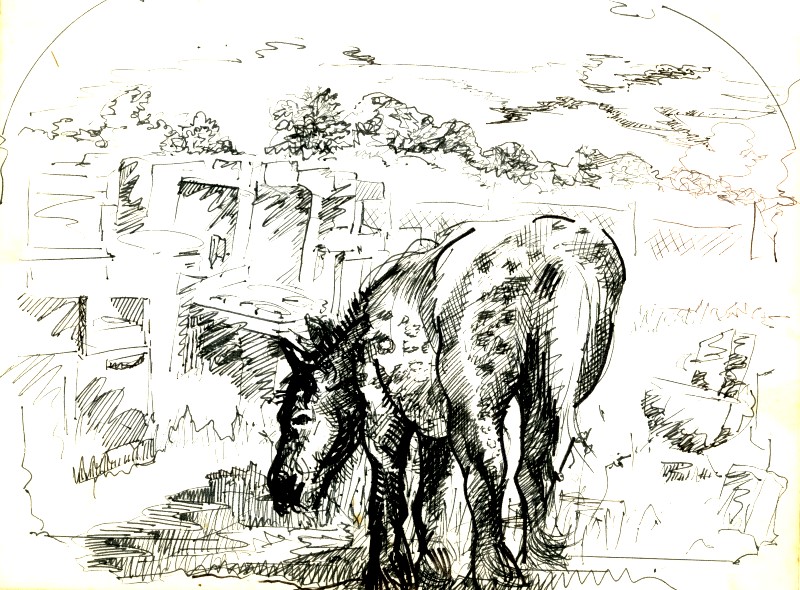

Either Massey or her husband walked alongside the buggy which was pulled by their 1300 pound horse Tony. A real speed demon, Tony raced away, easily covering 25 miles per day. The Massey’s felt finding a companion for Tony might calm him down a little, and when Nell the pony joined the group, she did just that.

“Everyone was so friendly,” Massey recalls.

People would walk with them for short stints offering them food, hay, gifts, a place to spend the night. Water to wash with, to cook with and to drink was always gladly accepted.

Massey continued her work from the road. From vegetables she made dye for her weavings over the night’s campfires. From post offices en-route she mailed her finished pieces to a museum that was showing her work.

She was, “always was” and is, after all, an artist.

Coming from three generations of artists, Massey believes “the process of creativity has to be unlearned.”

She is convinced there is “no such thing as a youngster who cannot draw. It’s innate.”

She insists she has “never met a kindergarten child who could not draw.”

Sadly, Massey tells of a time when her own artistic instinct was almost killed; she is thankful her mother didn’t let it happen.

“I remember in second grade we each got to make Christmas balls. I was so excited. I made (reenacting the circular motion with her hand in the air) big, big ones… About the size of my head.

“My teacher ripped them up, in front of the whole class,” she says.

The next day Massey’s mother went to the school and confronted the teacher with “My daughter comes from a long line of artists. She was excited, expressing her excitement with’ scribbles.’ Please do not kill her excitement.”

The teacher apologized.

Still, Massey worries that “through our (well-meaning) teaching process we often destroy the artist in us.”

She maintains that people unintentionally “kill the creative impulse. It’s like a delicate flower that can be stepped on and killed. (It is) hindered… by very well-meaning people.”

As an art teacher, Massey, defines her role as “healing the creative process in people.”

Well over 5000 students of all ages and experience levels benefited from her methods while she worked for the Tennessee Arts Commission and the Georgia Arts Council. Going “into the backwoods” to teach people with no previous training provided Massey with an “an incredible overview” of how artistic talent develops.

She claims that by simply looking at a person’s artwork she can determine at what age their creativity was stifled.

Her credentials are impressive. She received her Masters in 1972 from Yale University School of Art and Architecture; she received her Bachelor’s in 1970 from Philadelphia College of Art. She has taught for schools including the Georgia Arts Council, Emory University, Tennessee Arts Commission, and Yale. Presently she teaches at Cayahoga Community College. Her shows and exhibitions have been seen across the country, and Missouri, Georgia, Tennessee, Massachusetts and New York.

In the art classes she will teach from her home-studio this summer, Massey’s “goal is to help people along,” to undo any damage they have encountered and make sure their talents aren’t thwarted further. She describes her style as an “interesting way of drawing, a clean, uncluttered way of seeing.”

Starting with an eight week course in drawing and painting on Wednesday mornings for adults and Friday mornings for kids, Massey will also teach basketry classes on Monday mornings from her school located in the Cuyhoga Valley National Park.

The artist has planned classes toward the end of the summer designed to teach her students to sketch from nature. “The Artist’s Walk” classes will be taught from the park’s horse trail. Massey is excited at the prospect of hooking Tony to the buggy camper to pull supplies needed for the overnight sessions.

She admits she wants some of her classes to serve as a “kind of retreat for artists who need to work out of a creative rut, expand and build.”

She reasons “being out in nature heals.”

Massey sells most of her artwork. Like children, she says, she creates them, watches them develop, and then sends them on their way.

Her husband is involved with her work. “I design. He executes,” Massey explains.

But James wasn’t always an artist. An executive, he one day got tired of looking out the window at a brick wall. He gave up his career and now serves as his wife’s assistant.

He encourages his wife to sell her artwork in the manner of “the Indians who do sand art and then blow it” away into the air.

The Massey’s have been influenced by the American Indians, having lived one summer in a teepee as part of a group study. There they met their good friend, whose Indian name translates to mean “Ghost Horse.”

Hanging over the archway in Massey’s Studio 458, a sketch showing a line of moving horses is entitled “Hy Opa” which in the language of the Lakota Sioux means “the horse nation returns.”

“Many people” confides Massey, “share the same dream.”

Artist works for peace

World understanding through the exchange of art for the sake of the children.

Children’s Peace Foundation

Bernice Davidson Massey was living with her family in Tennessee when she learned her children, of Russian heritage, were concerned about prejudice. She decided “I’m going to do something about this; I don’t know what.”

Out of her frustration the “Children’s Peace Foundation” was born.

Going into the classrooms of her daughters, Sadie and Chloe, then aged nine and seven, the artist initiated a student art exchange. Her daughters’ classmates sent their drawings to children in the Soviet Embassy in Washington; the Soviet children sent back maps and trinkets.

Massey then completed an entire show of original basketry fashioned after the Russian cupolas. Her “baskets for peace” were filmed, the documentary was translated into Russian, sent to the Soviet Embassy and, she’s heard, the piece has been shown on Soviet TV.

“There was no cultural exchange (between the two countries) at the time,” Massey marvels.

Her peace efforts had just begun.

When her family moved to Georgia, Massey became involved with Leslie Schulten, founder of “Project Peace Tree.” That program originated when Schulten’s young daughter told her mother she was worried about the strained Russian-American relations.

“Project Peace Tree” resolved to send a tree to Russian students as a symbolic peace offering and asked local children to write letters to Soviet children, expressing goodwill and friendship. Each child enclosed their photograph with the Russian translation of “only friendship will hold the world together.”

The children received return letters from Russian children.

Pictures, buttons, tokens and information about America and the Soviet Union were exchanged.

Both Massey and Schulten, on Atlanta’s board For the Sister City Council at the time, were pleased when the pairing of Atlanta and Tbilisi as sister cities was confirmed.

Massey is now working toward another cultural exchange. She has made masks, cast from the faces of 200 American children, and has been invited by the mayor of Tbilisi to go to the Soviet Union and cast the faces of 200 Russian children.

“You don’t need words to express yourself with art,” concludes the artist, intent on expanding her mission of amity.